The Gallipoli story forms the foundation of a larger dialogue about reconciliation, immigration and the forging of friendship between Australian and Turkey.

In 1914 Europe entered World War I. In an attempt to gain a strategic advantage against the German, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman empires, the British authorised an attack on the Gallipoli peninsula. On the 25th of April 1915, the Anzacs landed at a logistically difficult position on the peninsula, an area surrounded by steep rock face and thorny scrub. The Anzacs, British and French suffered a large loss of life and made minimal advances, failing to resist a Turkish force that was easily reinforced and strategically effective. A defeat and evacuation of the Allied forces resulted, with retrospective accounts painting the campaign a disaster, partly attributed to the underestimation and misunderstanding of the Turkish offensive.

Image top of page: Adil Sahin, 94, with a peaked beret, Len Hall, 93, with the typical slouched, wide-brimmed headgear of the original Anzac. Image courtesy of Vedat Acikalin, taken in Gallipoli in 1990. Image above: Anzac Cove, Gallipoli, Turkey, 1915, Photographer: Dexter, Walter Ernest, Image P01130.001, courtesy of AWM.

Despite the events that transpired at Gallipoli, both sides retained a sense of humanity and a deep rooted respect for each other during the campaign. Such an esteemed sentiment is expressed by Charles Bean, an official Australian war correspondent with the AIF troops, in a poem for ‘Abdul’ in his The Anzac Book (London, 1916):

“We will judge you, Mr Abdul,

By the test by which we can –

That with all your breath, in life, in death,

You’ve played the gentleman”

- Turkish soldier carrying wounded Anzac soldier, Anzac Cove.

- Australian soldier offering a Turkish soldier a cup of water at Gallipoli, 1915, Image G00271 courtesy of AWM;

Moreover, this sentiment was expressed by Turkey’s first president, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who offered the following well-known words of comfort to the mothers who lost their sons at Gallipoli:

“Those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives…

You are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace.

There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side now here in this country of ours…

you, the mothers, who sent their sons from faraway countries wipe away your tears;

your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land they have become our sons as well”.

The Gallipoli experience reverberated with both these men, and their words have become a platform for reverence and a symbol of esteem between both nations. As such, the words of these distinguished men were chosen to be inscribed in the Australian Turkish Friendship Memorial Sculpture, providing a narrative to balance the more abstract symbolism of the sculpture itself. Bean’s words “a monument to great hearted men, and for their nation – a possession forever” are illustrative of the universal sentiment surrounding the sacrifices made in the name of war. The history as told by both sides has thus become inseparable from the sculpture’s intent: to highlight reconciliation and the forging of friendship between the two nations.

Such reconciliation has formed the basis for greater cultural and social links between the two countries, exemplified by Australia’s Turkish immigration history. Between World War I and II, Turkish migration to Australia was mostly prohibited under the Enemy Aliens Act (1920) and the subsequent White Australia Policy. Up until the 1960s, Turkish migration remained low, however, diminishing Western European migration served as a catalyst for the Australian Government to open its doors to Turkish immigrants. Simultaneously, in an effort to solve over-crowding and unemployment in Turkey, the Turkish Government agreed to an Assisted Passage agreement in 1967 with Australia which led to a sharp increase in Turkish migration: 970 Turkish migrants were recorded in Victoria in 1966 compared to 5,383 in 1971. Despite the resentment many new Turkish immigrants first faced when arriving in Australia at that time due to their non-Christian and Anglo-European background, this influx saw the Australian-Turkish relationship diversify and deepen into one of acceptance and inclusion.

Currently, there are in excess of 40,000 Turkish Australians living in Victoria. There are now many third and fourth generations of Australians with a Turkish heritage, in all walks of life, who are making a significant contribution to our community. The majority of the Turkish-Australian community lives in Broadmeadows and Coburg, with various religious groups, soccer clubs and political and community associations embedded in Melbourne’s cultural psyche.

- 1971. Migrants in their homes – Housing scheme at Thomastown for Turkish migrants – Sadik Yurtsever, Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia – 7427598

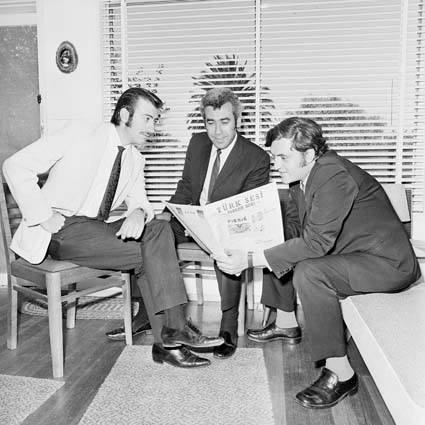

- The Turkish Voice Newspaper in Melbourne, image courtesy of SBS

The battlefields of Gallipoli was the first mainstream encounter between Turkey and Australia. 8,709 Australians, 2,701 New Zealanders and more than 86,000 Turkish soldiers died at Gallipoli, a devastating loss which has shaped both country’s national consciousness. Such loss has created bonds of solidarity between the Turks and Australians and has shaped the respect and friendship which has evolved over time. As Vedat Acikalin, a Turkish Australian noted ”as a child, we grew up with the stories and songs of Canakkale. But I had no idea until I arrived in Australia in 1973 how important the same campaign, the same battles, were for this country as well. For the losing side, it was the birth of a legend.”

25 April 2013: Ahmed Cetinkiran (left) and Turgut Kacmaz (middle). Turgut Kacmaz, the son of the last Turkish veteran to survive the Gallipoli campaign visited the Anzac Day Dawn Service at Melbourne’s Shrine of Remembrance as a guest of the Australian Turkish Institute. 77 year old Turgut made the journey to Australia that his father never could. He is dressed in an Ottoman uniform wearing his father’s original hat, called a Kalpak. He was quoted as saying ‘my father used to tell me no matter how fierce and ugly the war, that friendship is much sweeter and more powerful’. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

For sources and further related reading on the Gallipoli campaign and the history of Turkish immigration to Australia, see links below:

Gallipoli and WWI

gallipoli2015.dva.gov.au

anzacsite.gov.au

awm.gov.au

anzaccentenary.gov.au

rsl.org.au

nationalanzaccentre.com.au

anzacsonline.net.au

dontforgetthediggers.com.au

shrine.org.au

discoveringanzacs.naa.gov.au

army.gov.au

navy.gov.au

turkeyswar.com

future.arts.monash.edu/onehundredstories/

abc.net.au

slv.vic.gov.au

prov.vic.gov.au

australiansatwarfilmarchive.gov.au

mq.edu.au

cwgc.org

ww1westernfront.gov.au

ww100.govt.nz

nzhistory.net.nz

dtpli.vic.gov.au

gov.uk

Turkish Migration

museumvictoria.com.au

multicultural.vic.gov.au

vhd.heritage.vic.gov.au

nla.gov.au

archives.govt.nz

nationalarchives.gov.uk

austurkish.org.au